As open source has grown, it has also gotten more granular. Modern apps often depend on hundreds or thousands of open source packages, not counting the underlying operating system, which often contains hundreds or thousands of packages itself. So what do we know about the licenses in these increasingly large and complex software systems? The answer is: maybe not as much as users of the code would like.

How is licensing tracked?

So how do we know what licenses we’re taking advantage of under the hood? Historically, the answer was usually LICENSE files, or file headers (as recommended by the GNU project). This had the advantage of simplicity for developers, but subtle changes, copy-paste errors, and low standardization made it hard for large-scale consumers to process this into something useful. (I once got locked in a room for a week to produce the license notices for an Android-based device; it was lucrative for my law firm but oddly old-fashioned for everyone else involved).

More recently, many people (including me!) have recommended use of the SPDX license metadata standard to improve the machine-readability of licensing information. SPDX recently got a big win for their approach when the Linux kernel put SPDX headers in every file. This is simultaneously a big deal—since many projects look to Linux as a model—but also covers only tens of thousands of files out of millions across all of open source.

Modern package management tools like NPM and GitHub’s license API attempt to provide a useful layer of abstraction over file-based license information by providing licensing metadata and APIs. License geeks have hoped that these modern APIs, and further dissemination of license information, would give us something more useful—but have they?

What do we know about the quality of licensing information?

It turns out that when you dive deeper, the state of the information provided by the package managers and GitHub leaves something to be desired. There are two key ways license metadata is broken: first, by simply being missing; and second, by being inconsistent between different data sources.

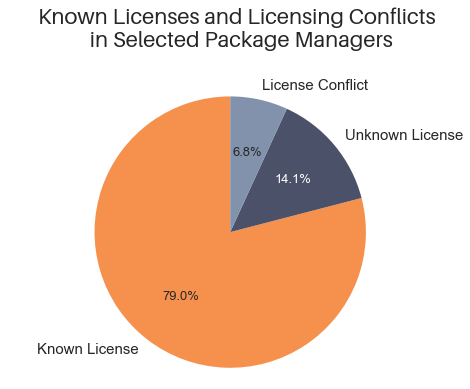

To the first point, missing data: in the simplest count, of the 2.4M packages tracked by libraries.io, more than a third (810,788) are either simply unknown, or “other” (usually an indication that GitHub has detected a license but is unable to determine what the license is).

Some of this information is missing because not all package managers provide licensing metadata. However, even if we narrow the question to large package managers that support license information and dependency information—specifically, the 1.1 million packages in Maven, NPM, Packagist, Pypi, and Rubygems—the missing information is still fairly large: over 20% of packages lack useful license information.

Determining what is missing is only the beginning. What about the quality of the information we do have?

As suggested above, one way we can check the quality of license information is by comparing what package managers think (usually based on a configuration file) and what GitHub thinks (based on parsing of files like LICENSE). In an ideal world, the package repositories and GitHub will always match—if the package manager says a package is BSD, then GitHub will also say the package is BSD, etc. In the large package managers where we can test this, the package managers and GitHub disagree about more than 82,000 packages (about 6.8% of all packages). So even when information is not missing, it may not be correct.

Do more widely-used packages have better license information?

Open source advocates, including me, have long argued that more attention generally leads to better software. Conversely, all package managers have a long tail of less-used packages that may not get as much scrutiny. Overall, if the “many eyes makes all bugs shallow” mantra is true, we’d expect to see that more-used packages have fewer problems in their metadata.

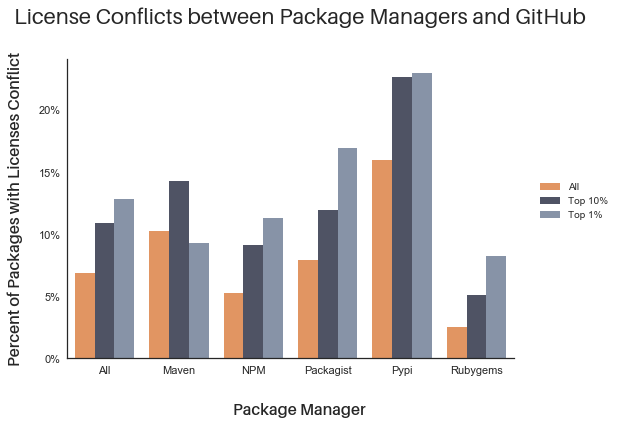

Using dependency information encoded by some package managers, and the libraries.io dataset, we can look at exactly this question. The results are encouraging, but not enough to make everyone sleep perfectly at night. The top 10% most-depended-on packages in the large repositories with licensing and dependency metadata have similar properties to the overall body—around 8.8% are lacking license information or are “other.” However, In the top 1%, things get better—only around 4% are missing license information. This is encouraging!

Unfortunately, the news is not all good. When we look at which licenses conflict, the most popular packages are actually worse—10.9% of the top 10% and 12.8% of the top 1% of packages have conflicting license information. We don’t have a firm grasp yet on why this happens. It could simply be because higher quality packages have more parseable license metadata, revealing problems not obvious in lower-quality packages. People trying to fix “unknown” licensing information may also contribute to the problem by fixing one set of data, without rigorously cross-checking with the other data source.

What’s the practical impact of conflicting licenses?

Around 60% of all packages (and 90% of the packages with known licenses) in the libraries.io data set are permissively licensed. Because of this, when there is a conflict between package manager and source code repository, in many cases both licenses will be permissive. This limits the practical impact of these conflicts.

The dominance of permissive licenses certainly doesn’t eliminate problems based on conflicting information. For example, slightly over 5,500 packages in the libraries.io data set are reported by one data source as permissive, and the other as some variety of copyleft. For many distributors, discovering previously unknown copyleft would be a very unpleasant surprise.

In addition, GitHub’s license scanning, which we relied on for the data in this blog post, is quite conservative, and so identifies about 15% of licenses as “other.” As GitHub’s tooling improves (or when this research is replicated with other scanners) we would expect to see fewer unknown licenses, but even more conflicts.

Where can we go from here?

The bad news is that there are lots of problems in even this very basic license metadata. The good news is that bad license metadata is usually pretty easy to identify and fix. While researching this post, Tidelift has already submitted patches for a number of the packages we use in our own tree! And we know from npm1k.org, the Linux Foundation’s efforts in the Linux kernel, and other experiments that most maintainers are happy to fix problems once they’re pointed out. But there is still a long way to go before this information is as reliable as we’d all like.

If you are interested in learning more, consider signing up for updates or following us on Twitter.

Thanks go to Keenan Szulik and Andrew Nesbitt for their help crunching these numbers.

50 Milk St, 16th Floor, Boston, MA 02109

50 Milk St, 16th Floor, Boston, MA 02109