Last week, I co-hosted a virtual roundtable with Justin Rackliffe, the Director of Open Source Governance at Fidelity Investments. The goal was to start a dialogue about what is—and is not—working when it comes to how organizations manage their open source supply chains.

Our guests were IT leaders from companies in highly regulated industries—mostly financial services—under constant pressure to maximize development speed while minimizing maintenance and security-related risk.

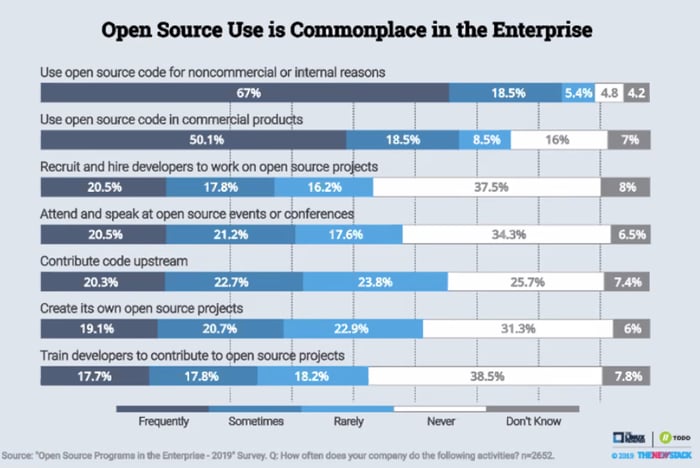

As Justin pointed out in his introductory remarks, most enterprise organizations have made open source software a centerpiece of their application development strategy because it allows them to work more quickly and efficiently. Justin cited this 2019 TODO Group survey showing that over 90% of organizations are using open source for noncommercial or internal reasons, and that over 77% of organizations are using open source in commercial products.

This maps very closely to the data we’ve found in our Tidelift research, where developers reported to us that 92% of their applications contain open source libraries. So open source is now everywhere, and for good reason.

But it isn’t always sunshine and roses.

Understand the provenance of open source you use

Justin compared the current state of the open source supply chain as somewhat akin to the food supply chain exposed Upton Sinclair’s classic book The Jungle, where “their tea and coffee, their sugar and flour, had been doctored; that their canned peas had been colored with copper salts, and their fruit jams with aniline dyes.”

In other words, if in the world of The Jungle, people didn’t really know what kinds of ingredients were being used in their food, today’s IT leaders don’t always know what kind of ingredients are being used in their applications.

Justin’s advice was that we should demand more information about the provenance of the components of the technology we use. We can ask this of those who supply software to us, we can ask this of those who are building software in our organizations, and we can supply this information to those who consume the products we build.

By elevating the standard for how much we know and discuss about the software components we use to build applications, we could help protect organizations from malicious actors trying to build backdoors into open source projects. We could help prevent maintenance crises resulting from tired, well meaning maintainers lacking the time or incentives to continue to keep their packages up to date. We could better navigate the complex maze of open source licensing, without exposing organizations to intellectual property risk.

Further, Justin made the point that we need to do this without having the effort become burdensome to the developers in ways that slow their progress. Developers shouldn’t treat open source like an all-you-can-eat buffet, but we also shouldn’t force them to chase down every single possible issue without regard to the level of risk.

In Justin’s words: “We don’t want our developers chasing noise. It’s expensive.”

Here are the slides Justin used for his presentation:

Create a list of known-good open source components

As we dove into the roundtable discussion, our participants—representing leading financial services organizations—shared how their organizations triage open source-related issues today.

One participant noted that while there are many tools out there that help uncover issues, there really aren’t good standardized processes for fixing them. In fact, as the result of using scanning tools, their organization currently faces a backlog of unresolved CVEs and other issues. They don’t really have good answers for how to get out from under the backlog, let alone a good process to handle new issues as they arise.

One big question that several teams were grappling with is whether to centralize the process for determining “known-good” open source components or decentralize and let developers fend for themselves.

Justin pointed out something very familiar, which is that most developers dislike centralized “command and control” approaches—and that they lead to a lot of “shadow IT” initiatives happening around the edges.

Another participant speculated that perhaps the right answer wouldn’t be found at the extreme of command and control on one side or “fend for yourself” on the other. Instead perhaps the right solution is a multi-pronged approach with some aspects that are centrally led, augmented by a set of tools that allow those in individual development teams to make smart choices without having to wait for approval.

At Tidelift, we’ve been working on this very problem. And we have looked for inspiration to the big tech companies, like Google, Amazon, LinkedIn, and Netflix, who have all talked publicly about their approach to open source management.

Many leading organizations of this class center their open source strategy on creating a catalog of known good components. This makes it easier for developers to choose a set of open source packages that will satisfy their organization's requirements today—and tomorrow. And if individual teams want to ski out of bounds, they can still do so, it will just take more energy to understand and evaluate the risk.

This approach has increasingly informed our product strategy at Tidelift. We are making it easier for more companies to be able to create and maintain a list of known-good packages without taking on the large time and resource commitment associated with doing it all themselves. After all, not everyone can invest in this to the level of a Google or an Amazon, and we can get more done by working together—and specifically, by partnering with upstream open source maintainers to get the job done.

We also talked about whether there are any good standard objective metrics around open source component health. One participant shared that their organization uses a securability metric that gives developers more information on the resiliency of a particular package and helps them make smart decisions about whether they could use that package safely. Another participant shared that they had established an internal viability scoring system with weighted averages from 0-10, shown by release version.

Develop clear policies for contributing to open source

We ended with a discussion about the importance of contributing to open source, and whether organizations see it as a priority.

Justin pointed out that when organizations do participate in open source communities, they “learn by doing” how to collaborate better. It helps organizations not only get the value from contributing, but also bring some of the best parts of open source into their organizational culture.

Another participant felt that it was important to be giving back to projects, but that their organization was very early in the process of beginning to contribute. He saw one additional benefit of contributing to open source: it helps individual developers build their reputations both inside and outside the organization, which ultimately helps them in their career.

As for managing your open source supply chain, Justin had some insightful parting thoughts.

“You can’t be the Isle of Dr. No,” he said. “You want to be the ‘Yes, and!’ People want to use these open source tools because they offer a lot of value. So don’t make security the boogeyman and get rid of the adversarial mindset.”

A special shout out to Justin Rackliffe for helping inform and guide the event! We appreciate everyone’s contributions and look forward to continuing the conversation.

50 Milk St, 16th Floor, Boston, MA 02109

50 Milk St, 16th Floor, Boston, MA 02109