In my last post, I talked about how much (or little!) we know about the licenses in the 30+ package managers and 2+ million packages in libraries.io, but tried not to talk about specific types of licenses.

In this post, I want to go a little deeper into one important type of license: those that require sharing of modifications under certain conditions, often called “copyleft” or “reciprocal” licenses. Examples include the well-known GNU General Public License and a spectrum of others, including the “network” Affero GPL (whose conditions may be triggered by use in services) and a variety of “weak” copylefts like the Eclipse and Mozilla licenses (whose conditions generally require sharing of fewer classes of changes).

There is no one measurement of the “state” of copyleft

I’m a copyleft license fan. I’ve led the drafting of one major copyleft license, actively participated in the drafting of at least four others, and given passing comments to more. So I think it is important to understand how copyleft is (or isn’t!) being used. If it is widely used, great; if not, supporters of the copyleft license should try to understand why that is, and react appropriately.

Unfortunately, there is no “one metric to rule them all” for the state of copyleft. In this post, I’ll use the libraries.io database to give a picture that combines both a per-project view (how many projects in total use a given type of license) with a per-repository view (how different language/technology families adopt different types of licenses).

By looking at both overall project counts as well as package managers, we aspire to meaningfully include ecosystems that may be smaller but still important in various ways, while avoiding a bias towards languages and ecosystems that encourage very small packages.

What’s the overall picture?

To understand the relative presence of various licenses in public package managers, the traditional reference point has been the core GNU/Linux operating system. As of a late December scan of the then-current Fedora 27 main package repository, over 31% were pure copyleft, and an additional 24% were multi-licensed with at least some copyleft components. (I look forward to the results of Debian’s push for machine-readable licensing information, so that similar numbers are easier to compute reliably for Debian.)

In total, of the packages in libraries.io with known licenses (about 1.17 million), slightly less than 8% (97,654) are some form of copyleft, or have a multi-license that includes some form of copyleft. This is weighted towards the largest package ecosystems, of course. To counter that, we looked by ecosystem, rather than by project. That yielded a similar result—the median package manager ecosystem is about 9% copyleft.

Breaking down the package managers

By slicing and dicing the package managers we can get a more complete picture.

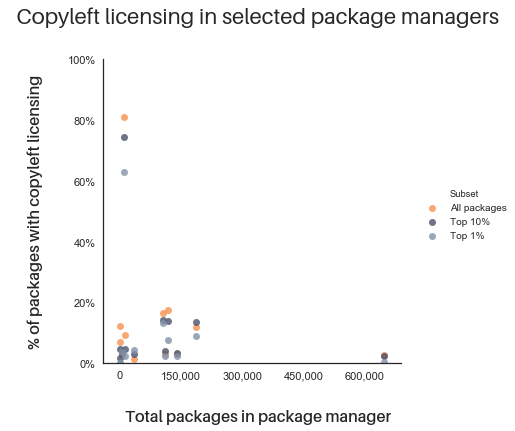

One option is to focus on the package managers with more than 100,000 packages and high-quality dependency information: npm, Packagist, Rubygems, PyPI, NuGet, and Maven (while size is not a perfect proxy for popularity, it is at least suggestive). These are similar to the 9-10% numbers we’ve already seen from the overall ecosystem: they range from 3-18% copyleft when looking at all projects in those managers (median: 8%), or 3-21% when counting only projects with known licenses (median: 12%).

Some smaller ecosystems are heavy users of copyleft, with percentages higher than Fedora’s 55%: Clojars is 74% copyleft (primarily Eclipse-licensed), and CRAN is 81% copyleft (mostly GPL). In addition, Wordpress and Melpa (the Emacs package manager) both lack license metadata, but when we’re able to get supplementary information from GitHub, packages in these ecosystems are overwhelmingly copyleft: 83% and 75%, respectively. Wordpress has about 54,000 packages; the other three mentioned here are in the 12-14,000 package range.

On the flip side, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that mobile and Apple-oriented package managers CocoaPods (39,000 packages) and SwiftPM (3900 packages) are both very permissive, with copylefts only a little over 1% in each ecosystem.

What about the most depended-on packages?

One fair critique of the comparison between the large GNU/Linux operating system repositories and other package ecosystems is that the Fedora/Debian packages are more curated, and therefore (arguably) a better sign of what the “best” developers or programs are using. This is a fair criticism—we’ve definitely found test packages and even spam in some of our research, which wouldn’t occur in the more curated operating system repositories.

To try to compare apples-to-apples and filter out less important packages, we looked at the top 10% “most depended” packages in large repositories with good dependency metadata—npm, Packagist, Rubygems, Maven, Nuget, and PyPI. This top 10% covers a smidgen over 130,000 packages, slightly more than double the size of Fedora 27. Here, there are two groupings: npm and Rubygems have 2% and 4% copyleft, respectively, while Packagist, Maven, Nuget, and PyPI are between 10 and 16%.

Repeating this analysis for the top 1% of packages, the numbers drop somewhat—npm goes to < 1%, gems to 3%, PyPI and Nuget to 8%, Packagist to 9%, with Maven staying fairly steady at 15%.

As the graph shows, regardless of how you slice it, with very few exceptions the measurements stay in the same cluster—around the low double-digits.

What about the various types of copyleft?

The definition of copyleft used for the numbers in previous sections cast a broad net, combining “network” copyleft (like AGPL, OSL 3.0, and EUPL), “weak” copylefts (like LGPL, MPL, and EPL), and the GPL. Breaking it down somewhat further:

Network copyleft is a very small portion of the sample. AGPL, OSL 3.0, and EUPL combine for slightly over 0.5% of packages in our sample, and only 0.3% in the top 10% of packages from the largest package managers. This is fairly consistent across package managers.

Depending on how you slice things (as described in the previous section), weak copylefts are 3-5 times more common than network, but still somewhat less common than strong copylefts. The distribution varies heavily by ecosystem. In some, weak and strong are similarly prevalent; in others (like Clojars and Maven) weak licenses are substantially more prevalent than strong, and in still others (like PyPI and Packagist) the reverse is true.

Where does this leave us?

These numbers tell a reasonably consistent story. Overall, copyleft flutters around 10% of open source, with some variation higher and lower within particular ecosystems.

By itself, this number does not tell us much: while this is a much lower percentage than in the traditional GNU/Linux operating systems, the absolute number of packages released under copyleft licenses continues to grow. Hopefully, though, it can serve as a useful anchor for further discussion.

If you are interested in learning about the nuances of open source licensing, consider signing up for updates or following us on Twitter.

50 Milk St, 16th Floor, Boston, MA 02109

50 Milk St, 16th Floor, Boston, MA 02109